TACOMA — Not far from the street corner where a maverick drug counselor started the nation’s first publicly sanctioned needle exchange, the organization he created decades ago is trying something new.

TACOMA — Not far from the street corner where a maverick drug counselor started the nation’s first publicly sanctioned needle exchange, the organization he created decades ago is trying something new.

Handing out free supplies for smoking drugs, including pipes.

Once a week, outreach workers from the Tacoma Needle Exchange distribute pipes like bubbles, hammers and stems out of a van parked near downtown Tacoma, placing them into brown paper bags along with soap, condoms, socks and naloxone, a medication that can reverse opioid-related overdoses.

In the same city where the late Dave Purchase began trading new syringes for used ones in 1988 to combat the spread of AIDS, his successors say they’re using “safer smoking supplies” to engage with and reduce certain risks for drug users. They’ve distributed thousands of sterile pipes since launching a pilot project in December 2020 on G Street, with the blessing of do-gooders from the Catholic Worker Movement who live and work in the neighborhood.

Handing out smoking supplies is potentially politically combustible and a legally uncertain step. While the possession and distribution of drug paraphernalia was mostly decriminalized by the state Legislature in 2021, and public health efforts can claim special status under the state’s constitution and statutes, with syringe sites legalized long ago, giving out pipes may still be considered a civil infraction that carries a $250 fine.

U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, a Florida Republican, made headlines in February when he accused the Biden administration of spending tax dollars on “crack pipes,” prompting the administration to clarify that a $30 million COVID relief grant aimed at syringe sites would fund smoking supplies like alcohol swabs and lip balm (to clean pipes and prevent open sores) — not pipes. There isn’t yet extensive U.S. data on smoking supplies as an intervention, according to researchers, though several studies abroad have indicated positive effects.

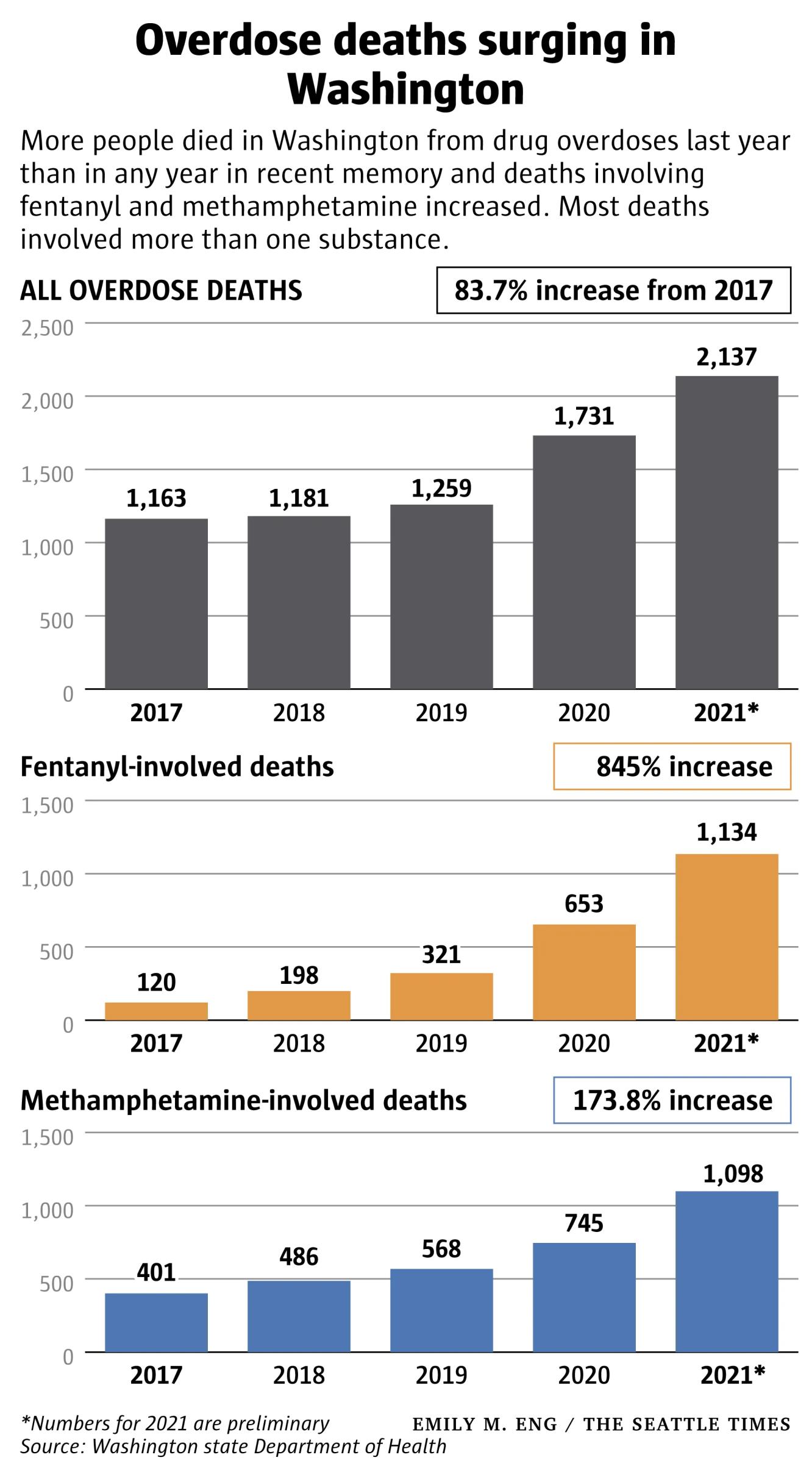

But proponents in Tacoma and beyond say the strategy is worthwhile, especially at a time when deaths related to commonly smoked drugs like methamphetamine and fentanyl are surging. They say distributing supplies like pipes can reduce the spread of diseases such as hepatitis, nudge people who inject drugs toward a less-harmful alternative, give users more autonomy and bring them into the orbit of services, including medication-assisted treatment.

Washington saw more than 2,100 overdose deaths in 2021, up 70% from 2019, per preliminary state data. More than half involved fentanyl, a superstrong synthetic opioid that’s flooded U.S. communities, and more than half involved meth (some involved both).

“The majority of people dying now from overdoses are smoking drugs,” Caleb Banta-Green, a researcher at the University of Washington’s Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute, said last month.

The Tacoma Needle Exchange, which links drug users to treatment, wound care and other aid, enrolled more than 700 new participants on G Street in its first year distributing smoking supplies there, accounting for 64% of participants, according to the organization’s initial data.

“If we just had needles, we would miss a lot of these people,” said Lupe Hurtado, an outreach worker and former drug user who credits programs like Tacoma’s with bringing people like her out of the shadows by treating everyone with respect and care. “There’s a stigma. … People feel like they can’t reach out. They feel alone, and that’s when people die.”

Though the exchange taps city, state and federal dollars for various aspects of its work, it’s using only private funds to purchase pipes and is distributing the supplies only a few hours each week, partly to collect data, executive director Paul LaKosky said.

Tacoma isn’t breaking new ground with smoking supplies; the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance in Seattle began handing out pipes in 2010, and some programs in other states followed suit. Yet the strategy is now gaining broader attention, partly because fentanyl has overtaken heroin and people are smoking it, said Lisa Al-Hakim, the Alliance’s director of operations.

With the COVID-19 pandemic elevating concerns about pipe-sharing, researchers like Banta-Green are speaking up about smoking supplies. Proponents were encouraged to see Congress authorize a grant focused on harm reduction, at least until it drew blowback from critics like Rubio.

LaKosky didn’t confer with local authorities about smoking supplies, in part because he didn’t want to put them in an awkward position, he said. But Tacoma Mayor Victoria Woodards last week said she approves, as does Anthony Chen, director of the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department.

“Especially when we are seeing an increase in the smoking of opioids,” Woodards said in a statement, smoking supplies “will provide safer alternatives for those who need them as they continue to move into drug support and treatment programs.”

“Anything that’ll keep people safe”

The operation on G Street is simple enough.

Once a week at 11 a.m., outreach workers park their van, set a table on the sidewalk, put a sharps container on the table for used needles and start greeting participants. Writing on clipboards, they record what supplies and service referrals each person receives, using anonymous identification numbers.

Their mascot is a chunky pit bull named Ransom who lounges on a dog bed by the van and waddles around to be petted. Some participants live in tents on G Street, but many people are housed, according to the organization, and many come from other neighborhoods, said outreach worker Jacob Ball.

“Today we have …” reads a white board on the table, listing items like body wipes and toothpaste next to drawings of pipes used for various drugs. The smoking supplies also include items such as special gum for dry mouths. Ball tries to ask each person not only what equipment they need but also what they know about their drugs.

Though fentanyl is typically sold in counterfeit oxycodone pills called “blues” or as powder, the dangerous drug also may show up in stimulants like meth and crack. The exchange distributes test strips to check drugs for fentanyl. Some users wrongly believe they can’t overdose by smoking, Ball said.

“Here’s a fentanyl test. Here’s how to test for stuff. You know how to use Narcan? Here’s how to use Narcan,” he recited, referring to a naloxone brand. “We’ve had a huge influence on the stimulant users coming to us.”

Resting in a wheelchair on G Street, Michael D. said he slipped into a coma and had a lower leg amputated last year after hitting an artery while trying to shoot heroin with a used needle. Now the 56-year-old smokes blues, he said.

Stories like that underlie the data pushing Banta-Green and his UW colleagues to raise awareness about safer smoking supplies, he said.

Fentanyl use spiked last year among respondents to the Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute’s biennial survey at syringe sites across Washington, with 42% saying they’d used it in the previous three months, up from 18% in 2019. Most reported using fentanyl intentionally (a change from prior surveys), and most said they’d smoked it.

Meanwhile, the rate at which younger people are dying from fentanyl-involved overdoses has grown. For people under 30, it doubled from 2019 to 2020 to 8 per 100,000, according to state data analyzed by the institute.

On one hand, smoking is less likely than injecting to spread diseases like HIV and cause injuries like abscesses and endocarditis, Banta-Green said. On the other hand, smoking can still trigger deadly overdoses and may be harmful in other ways, with more research needed, he said.

Whether the goal is to convert injectors or help smokers, the trends point to smoking supplies as a way to contact at-risk drug users and get them services, said Banta-Green, who co-authored a white paper in January.

“Anything that’ll keep people safe,” Michael D. said.

Community backing

When Jeff P. first heard about the smoking supplies on G Street, he reacted the same way many people do. “I thought it was just enabling,” he said.

Since a heroin overdose led him to switch to smoking drugs, the 36-year-old has come to appreciate the strategy more. “People are going to do it anyway, so them making it safer” can only help, he said.

That’s the basic idea behind syringe sites, hundreds of which have opened in response to the opioid epidemic. They’ve long battled the perception that they promote drug use, but decades of research have shown they’re safe, effective, cost-saving and “do not increase illegal drug use or crime,” according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. The CDC endorses such programs, citing a landmark study in Seattle that found that users of exchanges were more likely to stop injecting and five times more likely to enter drug treatment.

Forcing drug users into treatment en masse “can’t be done,” said Chen, the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department director, arguing the best approach is to “meet people where they are.” Referrals from the Tacoma Needle Exchange have resulted in at least 330 treatment starts since the organization teamed up with the Health Department in 2019 to provide on-demand access, according to the department’s records through 2021.

While pipes can be purchased legally in glass shops, under the assumption they’re going to be used for tobacco or marijuana, civil law in Washington still technically prohibits giving out drug paraphernalia on the street. That said, there’s an exemption for “the legal distribution of injection syringe equipment” via HIV prevention programs, and state courts have in the past deferred to public health authorities.

Tacoma’s exchange has multiple locations. For smoking supplies, the G Street site made sense partly because the neighbors were unlikely to object.

The area is a longtime hub for social justice activists. It’s where the late Bill “Bix” Bichsel, onetime priest at St. Leo’s Catholic Church, created the Tacoma Catholic Worker organization, whose members live on G Street and operate transitional housing there. The church runs a food bank. Catholic Community Services has a shelter and low-income apartments. Parishioners tend a cooperative garden.

Michael Sterbick, involved with Tacoma Catholic Worker for 30 years, says the distribution of safer smoking supplies jibes with all of that. Almost everyone has dealt with addiction, in one way or another, he said.

“Life is a bunch of relationships. You tear ’em down or build ’em up,” said Sterbick, who lives on G Street and goes by the nickname “Sandwich Mike,” because he hands out sandwiches to homeless people. “This whole community is about building relationships.”